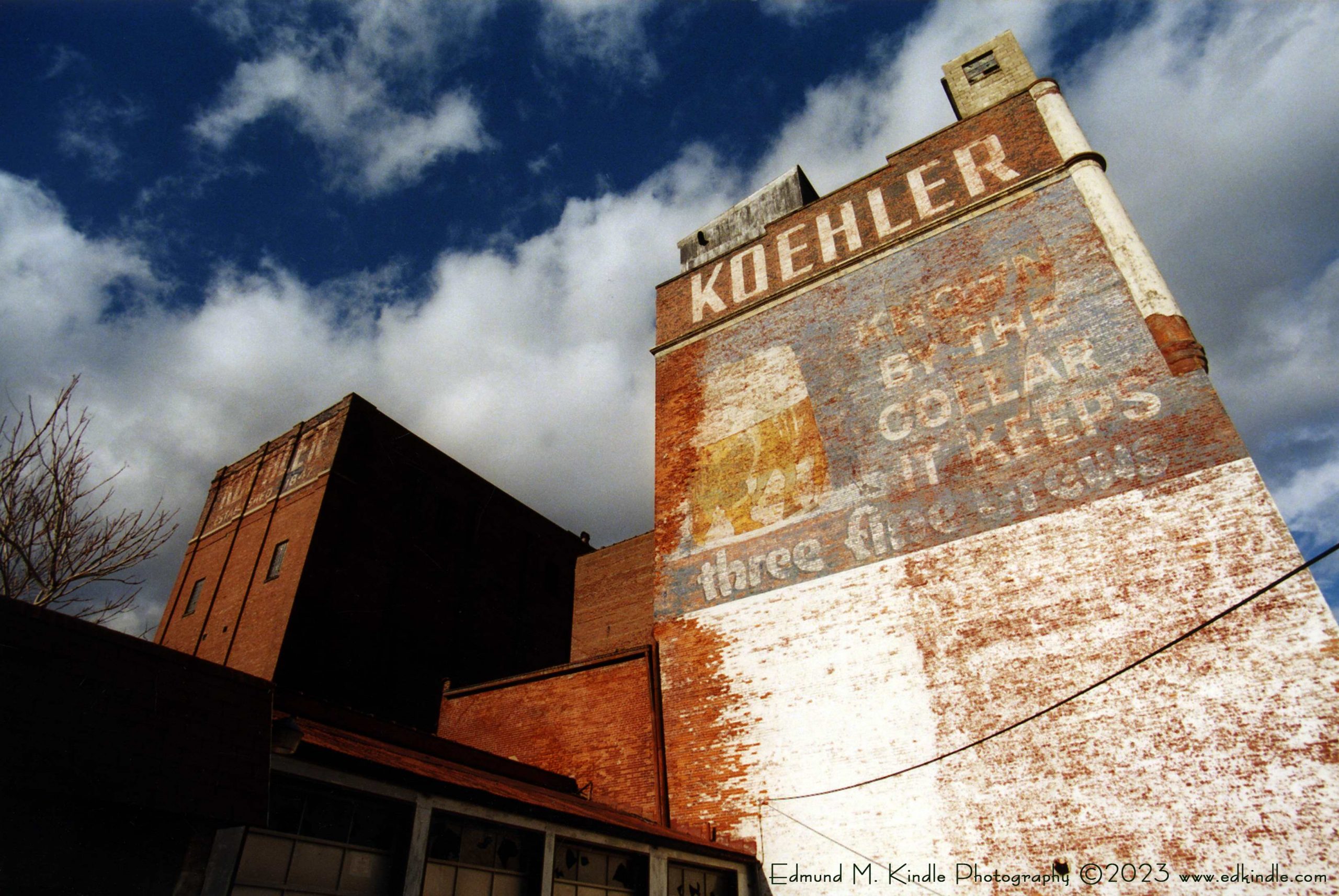

The Koehler Brewery

Growing up in Erie, Pennsylvania, few buildings were as iconic as the former Koehler Brewery – Erie Brewing Company’s buildings. The brewery closed in 1978 after a 90 year production run. First built on the site in 1855 subsequent additions took place over the years. Jackson Koehler started brewing in 1890 and his beers were nationally known, so much so that a rival brewer purchased the equipment, rights and recipes. Schmidt’s came in and removed all the brewery equipment and after many years and mergers now all is owned by Pabst Breweries.

I can remember for years driving or walking by the site, the white brew house, looking so majestic. Dwarfed by the rest of the site. Their main headquarters were located across State Street to the east and a tunnel connected them.

The buildings stayed empty for many years. Huge gaping holes where huge liquid storage tanks were removed allowed homeless persons and vandals access. The site was purchased and used for storage by a private individual for many years. We all wanted to know what was inside and explore. Little did I know back then, that someday I would get that chance.

Back years ago I was employed selling photography equipment on a consumer and professional level. One of my fellow employees was a lab tech who was also a photographer and we explored several local landmarks including Union Station. We had talked about the possibility to trying to gain access to the Koehler property several times. One day we decided to have a look around.

It turned out to be a fortuitous decision. As we approached the rear of the property, we happened upon several people having a discussion. They asked us who we were and what we were looking for and we flat out told them we wanted to get into the property for the purpose of photographing the insides of the compound. Honesty was indeed the best policy as it turned out the people we were speaking with were the new property owner and his engineers.

We were given permission to access the property provided that if we were injured in any way, we would forgo any attempts at an insurance claim. We readily agreed, shook hands on it and proceed to grab our gear. Over the fence we went.

It was everything we had hoped and more. A mix of existing untouched architecture, with areas of controlled demolition to remove brewing equipment and years of left over detritus from the previous owner’s hoarding and storage. Mix in decades of decay, with some fire damage and two slightly crazy photographers who had the run of the place, and you wound up with an awesome playground.

We spent every minute in the buildings we could over the next several months. We shot in good weather and bad. Sun or overcast. Summer to winter, Inside and outside. Personally I shot nearly 1000 images. Before you start thinking well that’s not that much given the size and scope of the project, remember this was years before digital became a big hit and well before any consumer grade DSLR’s were commonplace. I shot on a variety of color and black and white print films as well as slides and had to pay for all that film processing. This turned out to be a pricey adventure.

We covered the complex from the roof to the underground storage vaults and tunnels, to any and everything we could crawl into or climb up on. We scrambled up and down stairways that no one in their right mind would attempt to traverse, to standing next to 30 foot diameter holes where huge brewing vats were removed looking straight down five stories.

At one point we were contacted by the owner asking if we had been in a certain location. We told him we had indeed been standing there. It was an outside wall, four or five stories high, overlooking a catwalk that spanned the gap between two buildings. Now remember, this is two guys of a bit above average weight carrying about 50 pounds of camera gear each. We really hadn’t seen the reason for his concern, as we were, in many instances following the footprints of the engineers who preceded us in their inspection (except in this instance we hadn’t, and that’s what clued them in. They saw our footprints). When we went outside, we realized the reason for their concern, the outer wall was leaning well over two feet outward from the vertical.

At that point, we decided to be a bit more cautious. Which, as it turned out for us, was a relative term.

Our next foray was in the tunnels. Now remember, this is in a vacant, abandoned building with no power or lights of any kind other than what came in through windows or holes in the walls. We had head lamps, and flashlights, and when we took a photograph, the strobe on the camera would light up the entire room. It was actually pretty amazing because the walls for the most part underground were painted white, which reflected the light from the strobes all around the rooms making the many of the photos appear to have been taken in daylight. But most of our explorations underground were done in pitch black conditions.

One of the more extreme areas we encountered was pretty difficult to find. We had done some research and knew of a small spiral stairway in the old part of the brewery. We needed to find this as the stairway under the engineering building was broken and flooded out. After a bit, we indeed found it and it was small! We barely fit down it, shoulders and gear scraping down the sides. It led down to some tunnels and access corridors that opened into a larger central hub. We wanted to go but some of the tunnels were flooded. It was as though we both had the same crazy thought, looked at each other and said “hip boots”.

Before our next excursion, we had indeed acquired two pairs of wading boots. We went back down into the chambers, and proceeded to step into the water. Now the water was crystal clear when illuminated by our flashlights and headlamps, however, as soon as we moved, it silted up and we couldn’t see the floor. So we came up with a bit of a plan.

We first took photos, standing next to each other, again in total darkness, then grabbing the back suspenders of whomever was in front, the point person would take a careful step, keeping all our weight on the back foot until we could determine the next step was safe. Then transfer our weight to the front foot, and repeat. At times I used my monopod scraping the floor ahead as I moved. We had no idea if there were any drops in the floor or missing grates ahead under the water that might have been filled with decades of silt and dirt waiting to give way under pressure. This took several hours to get through all these tunnels and the entire time the water was up to the top of the hip boots. It was a challenge to keep the photo gear dry.

We eventually explored every flooded tunnel and even came across the tunnel that traversed under State Street to the original main office located on the east side. Halfway under the street, it was walled up 95% of the way and we could only see a small bit of the other half of the tunnel. The sad part was even here we were not the first, as graffiti was everywhere.

This was before the whole “urbX” or urban exploration fad took off. We were just photographers interested in documenting “what was left” of “what once was”, and were just excited to have an opportunity to be in a place that had lodged deep in our consciousness for so many years living here.

We explored the brew house, the engineering building, the coal tipple, the smokestack, the basements, the chilling rooms, the storage houses, the warehouses, the roofs, the tunnels, the shipping docks, the break room, anywhere and everywhere we could walk, crawl or climb we went and documented. We even climbed a three story metal spiral staircase bolted to the corner of the engineering building that sure didn’t look stable. It was in a word, exhilarating and led to one of the roofs next to the main smokestack.

We even found the “Rathskeller”, the legendary on site bar that served the company’s products that was supposedly provided for employees. Even though the destruction here was great with benches smashed, the mantle was still attached to the fireplace. There looked to be a small kitchen attached to the area with cupboards smashed and hanging askew. The small corner sink was unique, but any glass or mirrors were long broken out. They only close call we experienced safety-wise was above the Rathskeller.

(Rathskeller – Orig., in Germany, the cellar or basement of the city hall, usually rented for use as a restaurant where beer is sold; hence, a beer saloon of the German type below the street level, where, usually, drinks are served only at tables and simple food may also be had; — sometimes loosely used, in English, of what are essentially basement restaurants where liquors are served.)

In this attic, I was looking at the remains of what looked to be a marble or alabaster decorative surround and my foot broke through the ceiling. A quick grab by my exploration partner kept me from going all the way through the floor. This space was also interesting due to the large number of vintage school desks placed there for storage. We never found out why.

Some areas were remarkably intact even though they were exposed to the elements for decades due to huge holes cut into walls to retrieve equipment. Ornate cast iron staircases survived, but a few looked to be cut down. Probably when Schmidt’s took out the large brewing kettles. Other areas were completely demolished and broken down to rubble.

We found several cars and trucks that had must have been there for many years including an old Studebaker flatbed. There were large areas that held materials placed the by the previous owner. Either salvage materials or supplies for projects we couldn’t tell which. Very little brewery machinery was left. Some duct work for moving grain on the upper floors, and small vat in the main brewhouse, some dials and electrical panels, but most was gone.

There were also very few artifacts. I found an old book that contained a notation by someone that may have been a family member but after nearly 30 years I have lost track of it. That book was the only souvenir we took. We found only one empty half crushed Koehler beer case. On it, and throughout the complex there was an incalculable amount of bird droppings. We probably should have been wearing masks.

There was a bit of architectural salvage done by the new owners that they intended to work into the remodel of the building. The building corner stone and the eagle that graced the main entrance to the brewhouse as well as the iconic Koehler clock that said “Home of Koehler’s – There’s no better beer”. I have to tell you, standing on the roof, close to that clock, looking down State Street and across the city was a great feeling.

These elements ended up being part of a legal argument. I remember being told the buildings were too far gone and unstable to be resurrected into a mixed use complex and so they ended up all being torn down. The site was razed and eventually was purchased by the neighboring car lot. The last to be demolished was the smokestack. I don’t know how the companies involved fared but I was glad that fate gave me the opportunity to explore and document the site to at least keep it alive in memory through images. I decided after all this time it was time to share them here.

All images were shot hand-held with Nikon equipment. F4 & N90 camera bodies and a variety of Nikon lenses. Nikon speedlights were used extensively in the interior images and the infra-red focus capabilities performed flawlessly in pitch black conditions. Images were created on a variety of Kodak color and black and white films as well as Fuji print and slide films. There are a few images that I feel were technically inferior but I feel their content was important and have included them as part of the historical record.

I did some quick internet searches and it seems the Koehler name and brand have been reborn in Grove City, PA. A pair of brothers named Koehler (unknown if they are related to old Jackson) were able to get the rights and some recipes and start brewing the beers again with some new twists. I thought it funny because when I lived in Grove City after college, it was still a dry town and if we wanted to go to a bar, we had to drive a considerable distance.

I guess times do change.

Edit – Well everything is loaded. It took three galleries and 575 images. Some images I feel are very strong and will stand on their own. Many more are simply documentary and were compromised by the environment I was shooting in, or by my equipment limitations. Also weather had an impact on shooting the exterior shots (as anyone from Erie knows that blues skies can be rare in the winter). Many images were shot in near or total darkness & underground to boot. Remember this was pre-digital, so there were no instant previews. Everything I shot was on film and had to be processed and printed before I could decide what I was going to re-shoot. I edited this set down from nearly 1000 images. Overall I feel as a whole, the set stands up well for itself as an archive and record of the structure historically before it was razed. It is a shame that the buildings, at least the original brewhouse couldn’t have been saved. Some much of our past is just bulldozed over, never to reappear.

I am pleased that I was able to capture these amazing structures.

EMK